I'm going to try and write this without using the word lurid. Awe hell. Well, to late. I guess I'll just jump on board with the 90% of reviewers who made sure to bust the word out in the first paragraph of their reviews. It's not a very insightful comment but it is accurate. You see, the thing about be lurid is that its kind a hard to miss. Luridness is all surface. What I don't understand is why so many critics seemed surprised by this aspect of the film. Aronofsky is not exactly known for his subtlety. His films bludgeon, they assault. They are films about people on the edge and they reflect that anxiety visually.

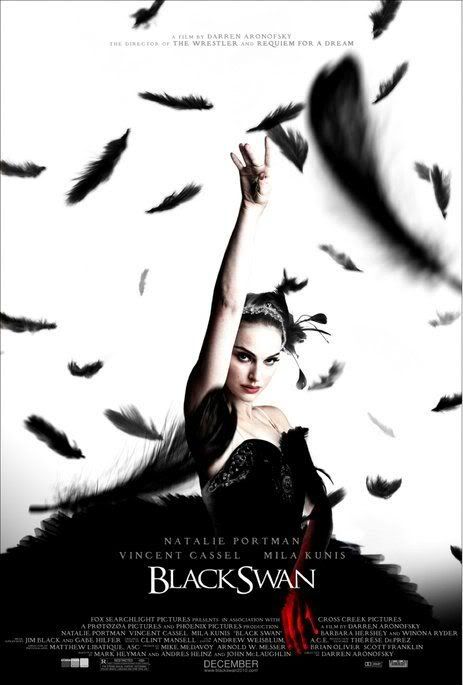

In Black Swan the person on the edge is Nina (Natalie Portman), a ballet dancer who has been relegated to small parts her entire career. She has skill in abundance but lacks, for director Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel), the passion of a true artist. She's a technician and though she longs to get the lead in Leroy's "re-imaging" of Swan Lake, he seriously doubts that she can pull of the devious Black Swan, though he knows she's perfect for the White Swan. This set the stage for the backstage drama that structures the narrative. It's familiar ground that anyone who's seen All About Eve (which should be everyone) will recall.

The setting really isn't that important however, and the heart of the film involves Nina's quick descent into madness. Or maybe that's a slow descent, or maybe she's mad from the beginning. Whatever, either way things are not good in Nina's brain. Like so many a suffering heroine before her Nina's troubles stem from sexual repression. In this case the repression is due to the isolation that has been imposed on Nina throughout her life by her mother, Erica (a very good, very unnerving Barbara Hershey). Isolated doesn't quite cover it. Nina has been sequestered, made to care only about what her mother cares for, ballet. A failed dancer, Erica lives through her daughter. She's a stage mother. A really creepy stage mother.

Leroy gives her the part despite his reservations and because, in the grand tradition of (fictional) choreographers/directors, he has a massive ego and thinks he can transform her himself. Oh, if he only new how fucked up she really is. Though he's a cad and has a long history of getting involved with his dancers (he must have spent his youth watching All That Jazz over and over), Leroy's treatment of Nina is surprisingly tender. Okay, so he forces his tongue down her throat in one scene but he really is doing it for her. I can't believe I just wrote that sentence but it is the truth. You see, Leroy is one hundred percent right about Nina. She is bottled up. He sees it in her dancing but we get to see its root causes, the aforementioned mother. What neither he nor Erica know is that Nina isn't just repressed but is suffering a psychotic break. Aronofsky visualizes this psychotic break by having Nina continually seeing herself in other people. No that's not right. Not in other people but as other people. This first occurs randomly with a stranger whom she passes on the street but soon she is seeing her own image in place of all the other women in the film: her mother, the previous prima ballerina Beth MacIntyre (Winona Ryder), but mostly in Lily (Mila Kunis), the new girl fresh of the bus from San Fransisco. As is necessary in these kinds of stories, Lily is everything that Nina is not: a free spirit, passionate but not obsessed with perfection, and most importantly sexually free and uninhibited. She attempts to befriend Nina and for a moment it seems like she may be the one who helps Nina come out of her shell. Then, after a late night of parting with Lily (probably her first night out ever), Nina arrives late for rehearsal to find Lily filling in for her. She's enraged and assumes immediately that the whole previous night was an attempt to make her late and thus steal the part from her. Despite assuring her that Leroy made her the back up and that there was nothing she could do about it, Nina still feels betrayed. Whatever progress might have been started for Nina's psyche is abruptly halted and her sickness is forefronted from then on.

This may make the film seem like it is primarily a "back stage" tale like the aforementioned All About Eve or Paul Verhoeven's Showgirls. While that element is there and it is of some importance, it is not at the heart of the film. Another frequent comparison is with Roman Polanski's Repulsion, another tale of a sexually repressed young woman who goes mad. It's a fair comparison but for me neglects to account for just how good Natalie Portman is in the role of Nina. There is in Nina a sadness that is missing from Carol (Catherine Denevue) in the Polanski film. This quality creates a point of empathy for Nina and elevates the material beyond the melodrama and horror elements that the film uses. Rather than just being a showbiz film or a horror film, Portman and Aronofsky turn it into a film about the fragility of identity. I was reminded most of another film I viewed recently, Robert Altman's underrated Images. Thinking of Images made think of the film that inspired it, Ingmar Bergman's Persona and it is that film that serves as the foundation for Black Swan. Like Bergman, Aronofsky isn't afraid to tackle challenging subject matter. Both films are consumed with questions of identity: how do we form it, what does it mean, and basically, who the hell are we.

Bergman was also capable of exuberant style, as Persona clearly shows. Underneath that style, as is the case with Aronofsky, is a tremendous humanity and compassion for his characters and the audience. I'm not trying to say that Aronofsky is on par with Bergman. Bergman is one of the finest filmmakers the world has ever seen and while I've liked all of Aronofsky's films thus far, it's still to early to say just how good he might become. He does though, like Bergman, seem compelled to ask the "big" questions. Whenever an artist, particularly it seems film artists, tackle these questions and take it seriously, there will always be those who side step it with criticism that focus on (perceived) weaknesses of the artist. So be it. If you want to focus on the sensationalism, or the use of cinematic stereotypes that's fine, just remember that those things are tools just like the thousands of others employed by filmmakers every day, and if you don't look at what they end up constructing...well, you're only seeing a portion of what's there. There's a myriad of critics who seem to take this approach; who spend more time calling Aronofsky names then discussing the work. I've liked him since I first saw Pi and I named Requiem for a Dream the best film of the first decade of the new millennium. Black Swan isn't as good as either of those pictures but it shows again that Aronofsky is unafraid of grand topics and grand style. In the current American cinematic climate that, for me, makes him one of the best and boldest of directors.

Ultimately Black Swan is a sad film. Behind all the special effects and horrific imagery is the story of a talented young woman who really is very sick. In the end we realize that none of what we've seen (i.e. what Nina has seen) has any basis in reality. Leroy only wants her to be great, Lily just wants to befriend her, and her mother is equally sad, having given up her chance at greatness (or even mediocrity) to raise a child, only to smother that child to the point where she has no idea who she is outside of the identity her mother's prescribed for her from birth.

No comments:

Post a Comment